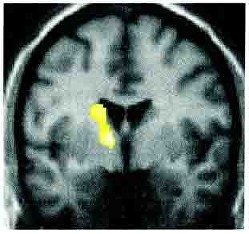

FND, is a problem with the ‘software’ of the brain. Scans are usually normal. When people with FND hear this they often wonder if the doctors is suggesting they are ‘imagining it’. The simple answer is ‘No – you are not’.

FND is due to a problem going on in the brain at a level that people CAN’T control – just like migraine.

It REALLY IS HAPPENING.

One of the big problems patients with functional and dissociative neurological symptoms experience is a feeling that they are not being believed. This is partly because many doctors are not trained well in functional disorders, including FND, and people have only begun researching them properly in recent years.

Some health professionals really don’t believe patients with these symptoms. That’s really upsetting and unacceptable when it happens. Others do believe there is a problem and are as keen to help as they would be if you had multiple sclerosis.

So if it’s a real condition but it’s not something you can see what is it?

FND is when the movement and sensation parts of the brain don’t function properly in the way you want them to, especially when you are trying to make them work. They usually will work better when movement or sensation is ‘automatic’, but that’s easier said than done.

Getting your head around this can take time. You have a condition that cant be seen on normal scans of brain structure, but you do have a disorder of your brain.

The following points may help you.

There’s more on this topic in one of the FAQs including – ‘Ive heard people describing FND as neuropsychiatric, doesnt this mean its psychiatric?’

In February 2022 I co-wrote a paper summarising all the scientific evidence showing why FND is NOT feigning or making up symptoms. I discuss these in a tweet thread which contains a free link to the article

‘Why FND is not Feigning or Malingering’ – our new @NatRevNeurol review and synthesis – with @M_Yogarajah and Mark Edwards https://t.co/4A3EHi9zfp. a thread… 1/ pic.twitter.com/VGOXviLXzJ

— Jon Stone (@jonstoneneuro) February 16, 2023

The answer to this question is undoubtedly (and unfortunately) yes, but it seems to be rare. In recent years, more cases where people have committed benefit fraud have come in to the public eye.

For example, one man was filmed playing football when he said he was in a wheelchair. Another was filmed lifting heavy bins when he said that he couldn’t carry anything.

In another case, a man who claimed he was blind and was sueing for damages was arrested for speeding on a motorway.

When patients who are malingering like this are examined, they can have some of the same positive signs as patients with functional symptoms but there are important differences.

They tend to have very inconsistent stories (because they are making up that too). They don’t have the same kind of stories to patients genuinely experiencing symptoms and there may be a legal case or other obvious reason for the symptoms. (although this does not mean that everyone with a legal case is making up their symptoms)

There are also some people who make up symptoms in order to gain admission to hospital or have an operation. When this happens it is called factitious disorder and by general consensus, it’s also a rare condition. It’s best thought of as a form of behaviour like deliberate self harm.

So, occasionally, people do make up symptoms and it can be difficult to tell. Some doctors (and sometimes patients) make a terrible mistake in thinking that most patients with functional symptoms are ‘making up’ their symptoms or ‘swinging the lead’.

Some patients with FND notice that their symptoms come and go in an odd way. This can lead some patients to wonder themselves if they are ‘doing it’. This is a very common experience and does not mean you are ‘doing it’.

If you are coming to this website for self-help, this is a very important subject to get right. Patients understandably don’t want to have a diagnosis that can be confused with malingering. I’ve explained above how rare malingering is but nevertheless some health professionals are confused about patients with functional symptoms and may have a poor attitude to your symptoms.

More commonly health professionals actually have a positive attitude to your symptoms but have difficulty in communicating this. Patients may become offended by health professionals even when they believe the problem and are trying to help.

Functional and dissociative neurological symptoms have been given many different names over the years.

Many of these labels are ‘psychiatric’ and are based on the idea that the symptoms are ‘all in the mind’. Psychological factors are often important to look at in relation to functional and dissociative neurological symptoms but the symptoms are not ‘made up’. Most experts believe that these symptoms exist at the interface between the brain and mind, between neurology and psychiatry, which is why it is difficult when people (and patients) ask “is it neurological or psychological?”. The evidence suggests it is both, and that actually this question doesn’t really make sense given what we know about how movement and emotion pathways work in the brain.

This list does not make easy reading , but it may help you to know about them.

Conversion Disorder – is a term popularised by Sigmund Freud and used in a standard US classification system of psychiatric disorders (DSM-IV). It refers to an idea that patients are ‘converting’ their mental distress into physical symptoms. Conversion disorder refers to symptoms of weakness, movement disorder, sensory symptoms and non-epileptic attacks. The principle of “conversion” is something that may apply to a small minority of patients but there is little experimental evidence for the idea in the majority of patients (usually the worse these symptoms are, the more distressed the patient is). In the revision of the psychiatric classification (DSM-5), the term functional neurological symptom disorder was added alongside and the requirement for a psychologically stressful event linked to the symptoms was dropped. In 2022 the DSM-5 Text Revision relegated the term Conversion Disorder to brackets after Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder – ie FND (Conversion Disorder) – reflecting increasing recognition that this is not a helpful overall label.

Dissociative Neurological Symptom Disorder – is how the symptoms are described in the International Classification of Diseases See the page on dissociation for more information.

Non-Organic – is a term doctors use for symptoms which are not due to identifiable disease. It implies the problem is purely psychological and honestly makes no sense at all. I wrote an article with my colleague Alan Carson about this. https://pn.bmj.com/content/17/5/417

Psychogenic – is a term quite frequently used to describe these symptoms, especially dissociative seizures and movement disorders. Again it implies that the problem is purely psychological.

Psychosomatic – has come to mean the same as psychogenic although its original meaning was to describe the way in which the body affected the mind as well as psychological processes affecting the body

Somatisation – suggests that the person has physical symptoms because of mental distress. The arguments here are the same as those for ‘conversion disorder’. Somatisation Disorder describes a situation where someone has a lifelong pattern of physical symptoms which are not due to disease.

Hysteria – is a term that has been around for 2000 years. It means the ‘wandering womb’ and comes from an Ancient Greek idea that women who had physical symptoms had a problem with their womb travelling around their body. In the 18th and 19th century it was used to describe any type of functional symptom or disorder. In the 20th century its use was narrowed more specifically to neurological symptoms and is now, thankfully, used more rarely.

Patients with FND have often had a raw deal from doctors over the last 100 years. Traditionally, neurologists saw their role as simply to diagnose the patient and then refer them to a psychiatrist for treatment.

Many neurologists have taken a very poor view of these sorts of problems over the years. There is a tendency among some neurologists to view these symptoms with suspicion. Other neurologists are sympathetic but don’t see themselves as having any skills to deal with the problem. Some neurologists jump to unwarranted conclusions about past psychiatric or traumatic problems which can be very unhelpful. Patients often pick up on these things which may be partly why they don’t believe the diagnosis the neurologist has made. Since I started in this area 20 years ago I would say that there has been a sea change of more positive practice towards FND. Younger neurologists are not willing to behave in the same way toward their FND patients and many are now interested and willing to do much more.

Most psychiatrists, unless they work closely with neurologists, also feel uncertain how to approach FND and often wonder if a neurological disease has been missed. I have discussed elsewhere in this website how psychologists and psychiatrists can be helpful in these conditions even when there is no depression or anxiety. Liaison Psychiatrists / Consultants in Psychological Medicine have specific training in this area and usually will understand these disorders.

Patients referred to psychiatrists with functional symptoms often feel that the doctor is just saying that its ‘all in the mind’. They understandably may feel defensive talking to a psychiatrist so the consultation may end up being unhelpful.

As a consequence of all these factors patients with functional and dissociative symptoms have often found themselves ‘falling through the gaps’ of medicine.

100 years ago neurologists and psychiatrists took a view that these symptoms were primarily a problem with the function of the nervous system and that while psychological factors could be important they may be absent and are not the only important factor.

Neurologists were interested in the diagnosis and treatment of the problem and wrote books on ‘functional nervous disorders’ with lots of common sense in them. The wheel is finally turning back to that point of view.

In my view, a lot of the difficulties in this area could be overcome if health professionals were better educated on the diagnosis and management of these disorders

We will be re-directing you to the University of Edinburgh’s donate page, which enable donations in a secure manner on our behalf. We use donations for keeping the site running and further FND research.