Since about 2012 there has been increasing evidence to support the role of physiotherapy as part of treatment for people with FND, especially those with functional movement disorders and limb weakness.

We have learnt in recent years that the kind of movement retraining needed in FND is different in many aspects to what is needed after a stroke or for someone with multiple sclerosis.

Functional Limb WeaknessIn FND movement is usually worse when someone is thinking or trying really hard to make a movement. But their ‘automatic’ movements, which they do when they are distracted or thinking about something else are usually much better or normal. That is the basis of some of the ‘positive’ signs of FND that enable the diagnosis to be made at the bedside, like Hoover’s sign or the Tremor Entrainment test.

FND-focused physio recognises this difference between voluntary and automatic movements and uses it to try to regain more normal movement patterns. So if you have a weak leg instead of trying really hard to move it, a physio might ask you to kick a ball, or focus on a spot ahead of you. For some people different walking patterns like ‘ice-skating’ or even jogging can help access better, more natural movement. You can read more specifics on these pages about the treatments limb weakness and movement disorder.

You can’t spend all the time trying to distract yourself – this is just a way to ‘open the door’ to more natural movement and better connections between brain and body that are part of improving from FND movement problems.

Most people with FND also have fatigue, weakness or pain which they find is made worse by activity.

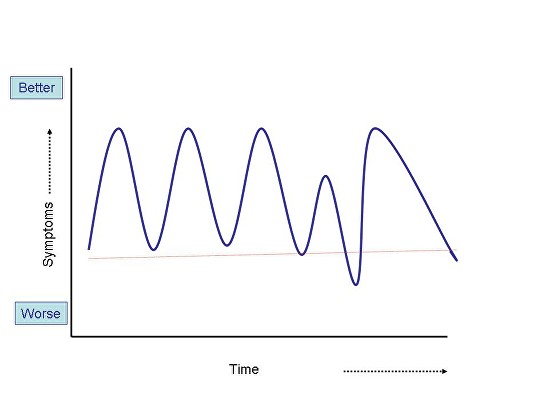

For many patients, the problem is not so much that they don’t do any activity, it’s that the activity they do is quite cyclical. So, one day you might be feeling a bit better, you rush round doing all the jobs you couldn’t do before because you were feeling so ill, but then you feel much worse again either later that day or the next day.

When your symptoms get worse again, it’s demoralising, you feel back to square one. The graph below shows what happens.

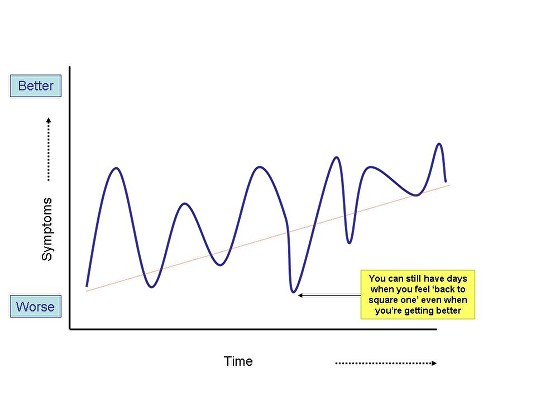

… You will still have days when you feel as if you’re “back to square one”. But if you’re improving slowly overall, that’s the main thing …

… Yes, activity makes the symptoms worse but no, you are not causing more damage. …

The principles of rehabilitation in this situation are to recognise that you probably are doing a bit too much on the good days and not enough on the bad days.

On a good day, set yourself a modest task, it might be a walk to the shop, it might just be a small job in the house. Make it something that is a bit less than you would do on your best day but more than you would do on your worst. Leave some petrol in the tank !

On a bad day try to do some minimum things like getting out of bed and getting dressed. If you feel up to it, leaving the front door and going outside, if only for a few minutes is better than staying inside all day.

If you stick to the SAME level of activity every day, hopefully you’ll find that after a while, perhaps a few weeks, this SAME level of activity may make you just a little less tired than it did before, or cause just a little less pain.

You will still have days when you feel as if you’re “back to square one”. But if you’re improving slowly overall, that’s the main thing (see graph below). But there is no getting away from the fact that doing this is tough. It’s as tough as losing weight or kicking a bad habit.

Physiotherapists and Occupational Therapists can often be very helpful in these situations. They are used to working with the day to day limitations that patients have regardless of their cause. They may be able to design a graded activity program that suits your particular symptoms and help you work through it. Graded activity has been shown to be helpful for some people with chronic fatigue and pain. You can read some more detailed information about it here.

Graded increases in activity is not for everyone and no one should feel forced into it. Some people need to stabilise their activity first using pacing techniques before they are ready to think about graded exercise.

Physiotherapists may also have a critical role in helping advise employers- so for example a return to work can be phased in partnership with the employer. Read more about work-related issues here.

If, after several weeks or months you feel things are definitely improving, be aware that recovery in FND can be fragile so be careful. Don’t rush to make lots of big life changes. Make any changes to work, school or home life slowly, and don’t make too many demands of your body

Psychologists may also be useful in helping you cope with the inevitable ‘ups and downs’ that go along with attempting this kind of rehabilitation.

What often goes wrong is that increasing activity leads to increasing symptoms, which makes the person think that they must be making their condition worse, causing damage to their back or muscles. The important thing here is that you’re not causing damage if you do it slowly. Yes, activity makes the symptoms worse, but no – you are not causing more damage.

The more activity you do, hopefully the less symptoms you will get (eventually).

For detailed consensus recommendations regarding physiotherapy for functional motor disorders click on this link which takes you to a 2014 article written by physiotherapists, neurologists, occupational therapy and neuropsychiatrists, all with experience of treating people with FND.

You may wish to share this with your physiotherapist to see if it gives you both new ideas.

There are some useful videos showing how physiotherapy works on the FND videos page. I’ve also reproduced some of them below

I also recommend Eva’s Story from a MotionRehab a private provider in the UK. I don’t endorse any private providers on this site but this film gives a great insight in to how creative physiotherapy that uses the person’s experience of “good” movement – in this case Eva is an amazing dancer – can help with recovery. https://www.motionrehab.co.uk/evas-story/

If you want to hear about FND physio from a professional, there is no one better than Glenn Nielsen, Senior Lecturer in Physiotherapy at St George’s Hospital, London. Glenn has led the field globally with new approaches to physiotherapy for FND including the recommendations on this page.

Here he is talking about FND to an audience of MS specialists, who need to know about FND because it can co-exist with MS sometimes or be mistaken for it. Its for health professionals but you might find it gives you some insights in to how FND focused physiotherapy works.

Thank you to Glenn Nielsen and Kate Holt for additional contributions to this page

We will be re-directing you to the University of Edinburgh’s donate page, which enable donations in a secure manner on our behalf. We use donations for keeping the site running and further FND research.