It’s common for patients with FND to wonder if the doctors have the right diagnosis. Read the page on ‘Misdiagnosis?‘ if you want to find out more about this.

This page on investigations is in the treatment section because people with FND can feel confused about what their investigations actually showed. The doctor may have mentioned some “abnormalities” and it may be helpful to have these put in context:

One thing that causes a lot of confusion is the presence on an MRI report of small white dots in the middle of the brain. These have a variety of names including high signal change, white matter change and small vessel disease. Sometimes they are even called ‘Unidentified Bright Objects or UBOs’.

These white dots start to appear with increasing frequency as you age in healthy people. Roughly, it’s OK to have one dot per decade. So if you are 35 you ought to have three or four dots, if you are 55 you may have 5 or 6. In fact once you get to your sixties then you will probably have a lot more than that. It’s a bit like grey hair.

You are more likely to have white dots if you are a smoker or have high blood pressure. There is also a suggestion that having migraine or depression makes them more likely to be present.

The problem comes when these white dots are interpreted in someone who has symptoms like weakness or numbness which are suggestive of Multiple Sclerosis (MS).

MS is diagnosed partly on the basis of seeing many white dots in the brain (in characteristic places not frequented by normal age-related ‘dots’). The radiologist may be clear that the dots are age-related or may write a report that is ambiguous and leaves everyone uncertain whether the scan is abnormal or not.

Sometimes all radiologists agree that a particular scan is uncertain. Sometimes one radiologist will report a scan with dots as normal and another will be unsure.

Sometimes a lumbar puncture is done to see whether there is evidence of inflammation in the nervous system.

Another situation where confusion can arise is when patients have MRI scans of their spine for symptoms.

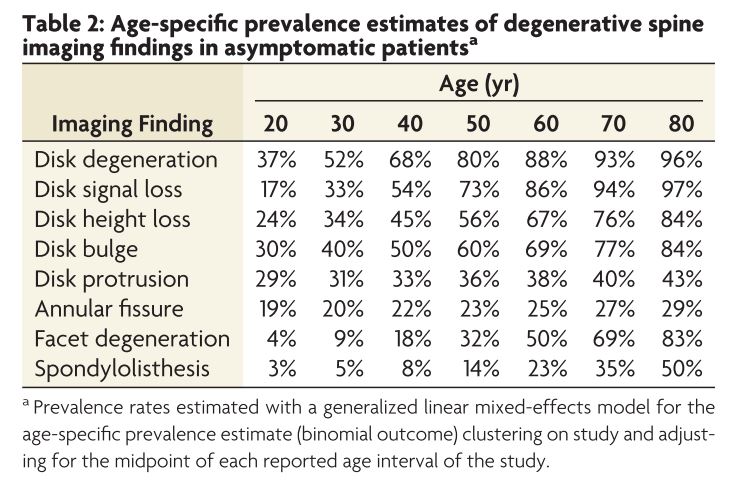

Like ‘white matter dots’, there are changes on spinal MRI that happen with age regardless of your age.

By the time you are forty, virtually everyone has a degree of ‘degenerative change’ in their spine. Studies have shown that patients with quite severe changes on their spine often have no symptoms.

It is certainly true that the majority of patients with spinal pain do not have any clear structural abnormality to explain their symptoms.

But often an MRI report will come back with quite alarming phrases like ‘degenerative changes’, ‘spondylosis’, ‘disc protrusion’, ‘osteophytic lipping’. All of these things imply a spine that is abnormal and damaged, and yet all these things, depending on their severity may be perfectly normal for your age.

Often the most important question is, is there evidence that any nerve roots or the spinal cord have been trapped. Even this can be tricky. Quite often in patients with non-neurological symptoms, like laryngeal problems, MRI has shown alarming looking problems with the spinal cord being squashed, and yet the patient has no symptoms.

The table below is a synthesis of all the studies that have looked at degenerative spine changes in healthy asymptomatic people with no back or neck pain. These findings are really common!

In addition to this studies in Germany have shown that finding disc bulges on a scan doesn’t even predict whether someone without symptoms is going to get back pain or not.

Many patients (and doctors), think that an MRI scan will sort out the diagnosis for the patient. Not only is this often not the case, but often a report of these kinds of normal and minor abnormalities can be actually harmful to the patient who leaves with a feeling that their body is damaged and abnormal with little chance of improvement.

Patients having blackouts may be sent for an EEG to investigate the cause. The EEG is a test which, when used properly, can be useful in some patients. It also has the potential to mislead.

Put simply, many patients with epilepsy can have a normal EEG (if they do not have an attack at the time of the test).

Many patients with dissociative seizures (and for that matter the general public) may have subtle abnormalities on their EEG which are irrelevant. Occasionally they may have a clearly abnormal EEG without having any attacks during the test. This still doesn’t mean they have epilepsy.

The only way to use an EEG to diagnose epilepsy securely is if the person has an attack during the test.

Most of the time this is not practical so epilepsy (and dissociative seizures) continue to be diagnosed on the basis of the patient’s and witness’ history.

We will be re-directing you to the University of Edinburgh’s donate page, which enable donations in a secure manner on our behalf. We use donations for keeping the site running and further FND research.